Bytecode

At each cycle of the RISC-V virtual machine, the current instruction (as indicated by the program counter) is "fetched" from the bytecode and decoded. In Jolt, this is proven by treating the bytecode as a lookup table, and fetches as lookups. To prove the correctness of these lookups, we use the Shout lookup argument.

One distinguishing feature of the bytecode Shout instance is that we have multiple instances of the read-checking and -evaluation sumchecks. Intuitively, the bytecode serves as the "ground truth" of what's being executed, so one would expect many virtual polynomial claims to eventually lead back to the bytecode. And this holds in practice –– in the Jolt sumcheck DAG diagram, we see that there are five stages of read-checking claims pointing to the bytecode read-checking node, and two evaluation claims folded into stages 1 and 3.

Each stage has its own unique opening point, so having in-edges of different colors implies that multiple instances of that sumcheck must be run in parallel to prove the different claims.

Read-checking

Another distinguishing feature of the bytecode Shout instance is that we treat each entry of lookup table as containing a tuple of values, rather than a single value. Intuitively, this is because each instruction in the bytecode encodes multiple pieces of information: opcode, operands, etc.

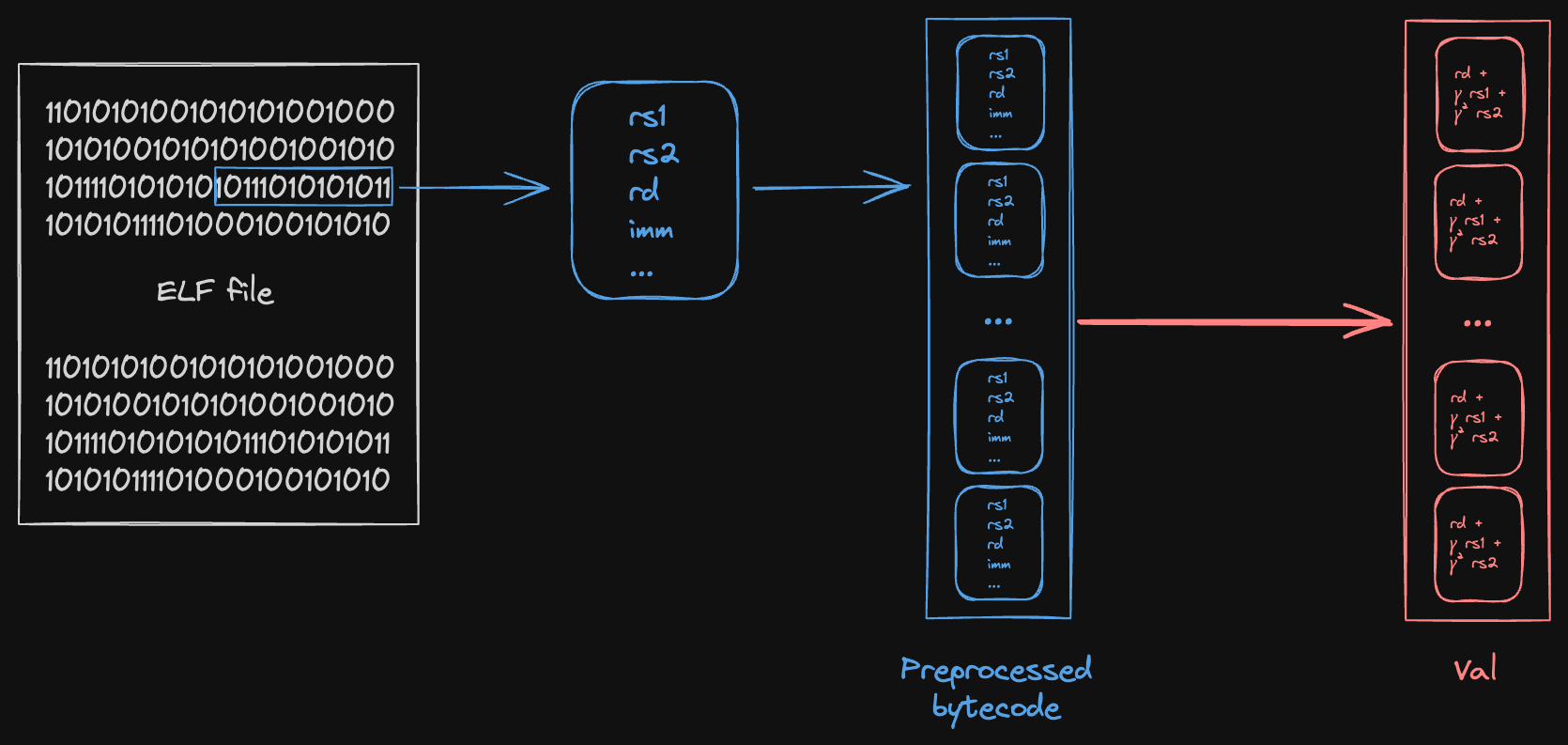

The figure below loosely depicts the relationship between bytecode and polynomial.

We start from some ELF file, compiled from the guest program. For each instruction in the ELF (raw bytes), we decode/preprocess the instruction into a structured format containing the individual witness values used in Jolt:

Then, we compute a Reed-Solomon fingerprint of some subset of the values in the tuple, depending on what claims are being proven. These fingerprints serve as the coefficients of the polynomial for that read-checking instance.

-evaluation

-evaluation claims for the program counter are folded into the multi-stage read-checking sumcheck rather than being handled separately. There are two claims:

- raf claim 1: From the Spartan "outer" sumcheck, folded into Stage 1 with weight

- raf claim 3: From the Spartan "shift" sumcheck, folded into Stage 3 with weight

The polynomial in the context of bytecode is the expanded program counter (), which maps each cycle to the bytecode index being executed. This is distinct from , which is the ELF/memory address.

Batching read-checking and -evaluation together

The bytecode read-checking sumcheck combines claims from five different sumcheck stages into a single batched sumcheck, using two levels of random linear combinations (RLCs):

- Stage-level RLC (using ): Combines the five stages together

- Per-stage RLC (using ): Combines multiple claims within each stage

The five stages are:

- Stage 1: Spartan outer sumcheck claims (program counter, immediate values, circuit flags)

- Stage 2: Product virtualization claims (jump/branch flags, register write flags)

- Stage 3: Shift sumcheck claims (instruction operand flags, virtual instruction metadata)

- Stage 4: Register read-write checking claims (register addresses)

- Stage 5: Register value evaluation and instruction lookup claims (register addresses, lookup table flags)

Additionally, bytecode claims for the program counter are folded into stages 1 and 3.

Combined Sumcheck Expression

The overall sumcheck proves the following identity:

where:

- ranges over bytecode indices (address space)

- ranges over cycle indices (time dimension)

- is the read access polynomial indicating cycle accesses bytecode row

- is the stage-specific value polynomial encoding instruction data

- is the identity polynomial that converts a bytecode index from binary form to the corresponding field element (used for claims)

- is the stage-folding challenge

- challenges are used within each to combine multiple sub-claims

Note that the claims treat the expanded program counter as , not UnexpandedPC.

Stage Polynomials

Each of the five claims has a corresponding polynomial that encodes different instruction properties. Using per-stage challenges , these are defined as:

Stage 1 (Spartan outer sumcheck):

Stage 2 (Product virtualization):

Stage 3 (Shift sumcheck):

Stage 4 (Register read-write checking):

Stage 5 (Register value evaluation and instruction lookups):

where:

- is the instruction's ELF/memory address (not the bytecode index )

- equals 1 if instruction has destination register , and 0 otherwise (similarly for and )

- Various boolean flags indicate instruction properties

Instruction address

Each instruction in the bytecode has two associated "addresses":

- Bytecode index : its index in the expanded bytecode. "Expanded" bytecode refers to the preprocessed bytecode, after instructions are expanded to their virtual sequences. This is what the polynomial uses to indicate which bytecode row is accessed.

- ELF/memory address : its memory address as given by the ELF. All the instructions in a virtual sequence are assigned the address of the "real" instruction they were expanded from. This is stored as part of the instruction data in bytecode row .

The bytecode index is used for addressing within the sumcheck (the variable in the double sum). The ELF address is used to enforce program counter updates in the R1CS constraints, and is treated as a part of the tuple of values in the preprocessed bytecode.

The "outer" and shift sumchecks in Spartan output claims about the virtual UnexpandedPC polynomial, which corresponds to the ELF address. These claims are proven using bytecode read-checking (specifically, they appear in the Stage 1 and Stage 3 value polynomials).

Flags

There are two types of Boolean flags used in Jolt:

- Circuit flags, used in R1CS constraints

- Lookup table flags, used in the instruction execution Shout

The associated flags for a given instruction in the bytecode can be computed a priori (i.e. in preprocessing), so any claims about these flags arising from Spartan or instruction execution Shout are also proven using bytecode read-checking. Circuit flags appear in Stages 1, 2, and 3, while lookup table flags appear in Stage 5.

Sumcheck Structure and Binding Order

The bytecode read-checking sumcheck proceeds in two phases:

Phase 1: Address Variables (first rounds)

In the first rounds, address variables are bound in low-to-high order. During this phase:

- The polynomials for each stage are bound, eventually reducing to scalar values

- Intermediate "F" polynomials are computed: , representing the weighted frequency that each bytecode row is accessed

- These F polynomials are also bound during the address phase

The sumcheck univariate in this phase has degree 2 (quadratic).

Phase 2: Cycle Variables (final rounds)

In the final rounds, cycle variables are bound, also in low-to-high order. During this phase:

- The polynomial is computed as a product of chunked one-hot polynomials:

- Each stage uses a

GruenSplitEqPolynomialto efficiently handle the per-stage evaluations - The bound and values from Phase 1 are used as coefficients

The sumcheck univariate in this phase has degree .

The chunking parameter is chosen based on the bytecode size to balance prover time and proof size. Larger reduces the number of committed RA polynomials but increases the degree (and thus the cost per round) of the sumcheck.

One-hot checks

Jolt enforces that the polynomials used for bytecode Shout are one-hot, using a Booleanity and Hamming weight sumcheck as described in the paper. These implementations follow the Twist and Shout paper closely, with no notable deviations.